Soundscapes

|

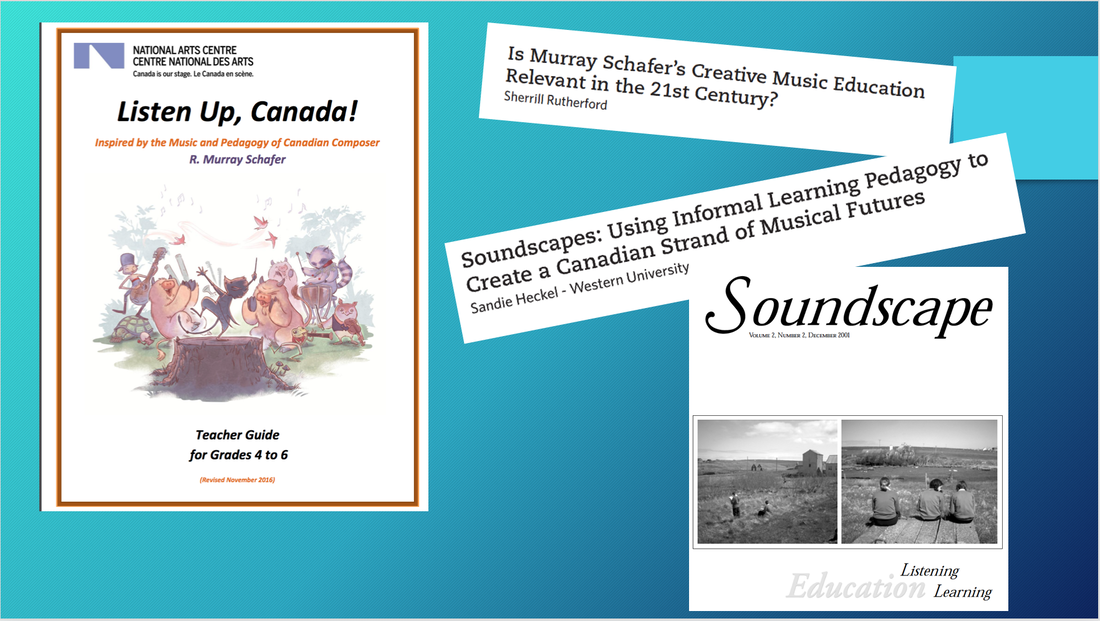

In the 1970’s, Canadian composer, educator, and soundscape pioneer R. Murray Schafer began asking: Why is school music education disconnected from student lives and experiences? How can musical endeavors help us listen critically to the world around us, and, perhaps more importantly, to each other? While Schafer’s main intentions in developing an approach to music-making that seeks to honor listening and creating with and among the world may not have been to interrogate assumptions, power structures, inequities, and stereotypes, he certainly articulated a need for change in the classroom.

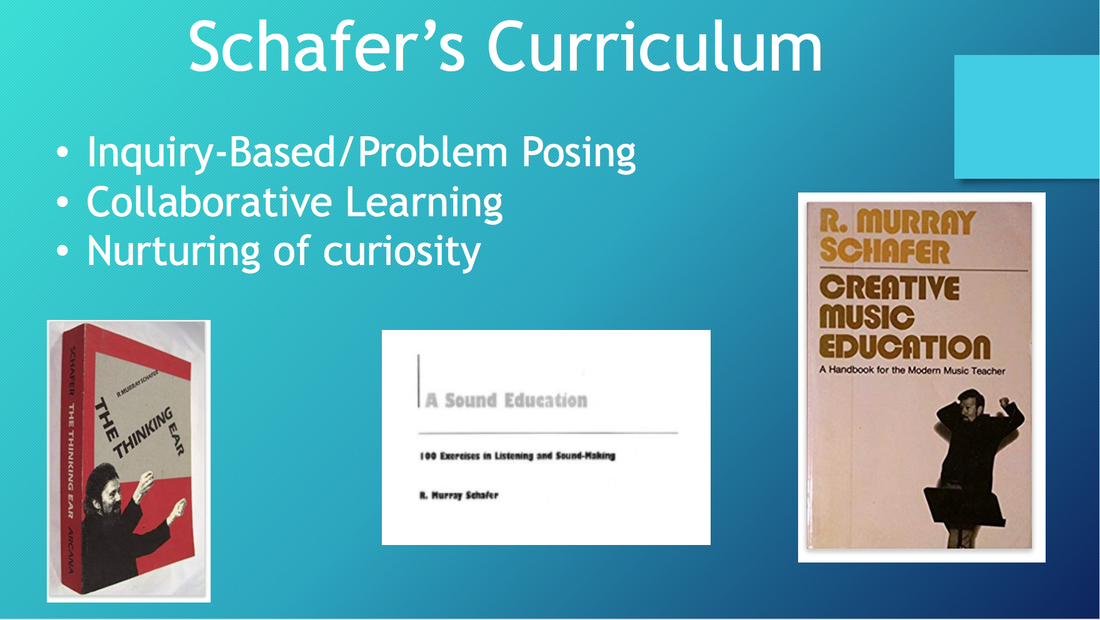

Schafer began his exploration of soundscapes in the late 1960’s during a wave of international activity surrounding creativity in the classroom. The Manhattanville Music Project was being explored as a response to declining participation in school music programs in the United States and composers such as Paynter, Davies, and Self were working in classrooms in the United Kingdom. The MMCP began by “getting young children to listen to and use the sounds of their own lives and environments as the basis of what were called ‘sound compositions’” (Regelski, 2011, p. 30). Students were encouraged to learn by doing and explore all sounds, including non-traditional sounds from their own environment. Regelski argues that “all students gain new and valuable skills and attitudes, among which, in particular, is the ability to listen to music with ‘new ears’” (p. 32). Soundscapes have become more common in music classrooms as a way to encourage students to compose electronically without the restraints of standard notation. As Schafer began to work in North American classrooms, he sensed a lack of creativity, an unresponsiveness to community, and a disconnect from students’ lives in the curriculum. In the 1970’s, he felt that a revolution in music education might be around the corner, but instead it appeared to him that North America took a step backward, reverting to music education that was about reproduction rather than discovery and a multiplicity of ways to understand and explore the world. As a response, Schafer wrote and disseminated an approach to music education that sought to honor listening and creating within and among the world as a primary approach to music-making. One key element of his curriculum was the use of soundscape composition as a way to connect school and community. Schafer (1992) defines soundscapes as “the total field of sounds wherever we are” (p. 8) and suggests that they urge us to listen to the world with “greater critical attention” (p. 11). Schafer leaves the choice of how to interpret soundscape composition in the classroom open to the educator and students, providing guiding frameworks, but not prescriptive, functional directions. Despite originating several decades ago, elements of Schafer's curriculum are still relevant in schools today. Historically, soundscapes have been present in music composition through the work of individuals like R. Murray Schafer, Barry Truax, Hildegard Westerkamp, and Pauline Oliveros, but they have also been present in ecological studies where soundscapes are used to discover "soundmarks," unique sounds that makeup the acoustic signature of a community. BENEFITS OF SOUNDSCAPES

|